I recently finished reading Esther Duflo and Abhijit Banerjee’s “Poor Economics.”

I have at least three topics in my mind from this reading and will need to discuss them in separate posts:

- The concept of a Poverty Trap and its application.

- The value and applicability of Randomized Control Trials (RCTs).

- The value of foreign assistance for poor countries and the conditionality of that value on exactly what is done with foreign assistance resources.

I might be able to address the last two bullets jointly in a future post, given current trends in US foreign assistance towards evidence from RCTs. In this post, however, I will focus on Poverty Traps.

Duflo and Banerjee describe poverty traps as follows:

“There will be a poverty trap whenever the scope for growing income or wealth at a very fast rate is limited for those who have too little to invest, but expands dramatically for those who can invest some more. On the other hand, if the potential for fast growth is high among the poor, and then tapers off as one gets richer, there is no poverty trap” (p.11).

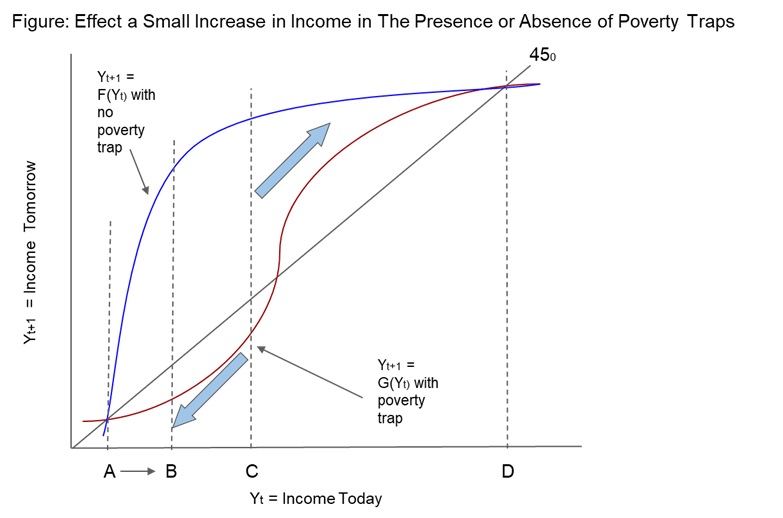

Adapting figures 1 and 2 from their book, in the figure below, function G (the S-shaped curve) represents a situation where an individual faces a poverty trap, if their income is currently below the level C. In that situation, a boost in income from say, income level A to income level B, is insufficient to support a sustainable increase in income over time and income levels will tend to fall back to A. Function F, on the other hand, represents a situation where an individual faces no poverty trap at any income level. A boost in income above the income level A would allow the individual to continue investing until income level D is reached (sustainable levels of income are those where Yt+1 = Yt, that is, where the function that maps Yt+1 to Yt crosses the 45° line).

The concept of a poverty trap is at the center of their book. The authors argue that, in a situation where there is a poverty trap, foreign aid can be of assistance to allow people to climb out of poverty. In a situation where there is no poverty trap, there is little justification for foreign aid.

They argue that whether there is or not a poverty trap – and, therefore, whether foreign aid is justified – is an empirical question that needs to be answered with evidence for any particular situation, and that it cannot be answered generally for all situations.

They contrast their position with economists that advocate more broadly for foreign assistance, or even greatly expanding it (e.g. Jeffrey Sachs in his well known book The End of Poverty) and other economists that largely oppose it (e.g. William Easterly in his also well known book The White Man’s Burden)¹.

Much of the remainder of the book is spent looking at particular cases and whether they show evidence of a poverty trap or not. Those cases pertain to hunger, health, schooling, family planning, risk, access to credit, savings, and entrepreneurship. Evidence is collected typically from RCTs.

In some cases the authors find evidence of a poverty trap, in others they do not. Their main message seems to be that aid can be effective if directed to projects where there is evidence of impact, under conditions where there is evidence of impact, implemented based on evidence of what works and what doesn’t, and avoiding what they call the “three Is:” ideology, ignorance and inertia.

As previously mentioned, there is much more to this book and I hope to come back to it in future posts. But for this post, I want to register a few thoughts on the poverty trap concept and its application to foreign aid.

First, if poverty traps are looked at as circumstances that certain individuals face and that impede them from overcoming poverty, they could exist in both rich and poor countries. If so, the difference in the presence of poverty between rich and poor countries would need to be explained by: a) relatively more people facing poverty traps in poor countries than in rich countries; or b) better standards of living for the poor facing poverty traps in rich countries than those in poor countries, due to other factors such as government assistance; or c) both. The question is then whether foreign assistance should target helping people overcome poverty traps or helping reduce the existence of poverty traps in the first place. The book’s last chapter, on policies and politics, can be interpreted as arguing that there is space for direct assistance to the poor, and that these changes can, overtime, affect the prevalence of poverty traps (by affecting political and economic institutions from the bottom up).

Second, if we study a poor country and come to the conclusion that there are few poverty traps and that the poor are poor because of their own choices, Duflo and Banerjee would seem to suggest that there is little that foreign assistance can or should do and that most economists (from Easterly to Sachs) would likely agree: in this scenario, the poor were given a choice and they chose to be poor, it is their right, we have no place in imposing anything different. Is this really the case? What about the children that are being affected by the choices of their parents? What about inter-temporal inconsistencies in preferences: would the current behavioral science literature suggest there would still be a value in assisting the poor to address those inconsistencies? Are there externalities where the choice of someone to be poor affects the well-being of the rest of society, or would attempting to affect those choices just be stepping on individual liberties? I have not given any thought to these questions but leave them here for rhetorical purposes, potentially to address them in the future.

Third, having grown in poor countries with large inequalities of income (Brazil and Paraguay), I always thought that exposure to the consumption habits of the rich negatively affected the choices made by the poor. The greater the income inequality in a country, the more it would seem the poor are routinely tempted to make consumption choices they cannot afford. Similarly, those living in poor countries are routinely exposed to the living standards of rich countries through movies, television, commercials, social media, tourism, trade; with potentially a similar effect on the consumption and investment choices made by those living in poor countries. It would seem this would generate an added deterrent to poor country saving and investment choices, relative to those faced by countries who grew at the forefront of technological development. Is there anything rich countries can or should do to help poor countries deal with this effect that they may not have suffered themselves? Again, the question is rhetorical. I may give it some thought in the future.

- The debate between Easterly and Sachs has served as a reference for the discussion of the value of foreign aid for over a decade. I actually had the opportunity to provide both readings to students of mine in a course I gave in 2007 on Foreign Aid at the Catholic University of Rio de Janeiro, shortly after the books came out.

References

Duflo, Esther and Banerjee, Abhijit V. 2011. Poor Economics. A Radical Rethinking of the Way to Fight Global Poverty. New York: Public Affairs.